Learning Python

1. Intro

1.1. The problem with learning Python

Learning Python is terrible.

All tutorials start with the amazement that you can have variables (WOW!) to

which you can assign values(Hurray!!). And, although I forced myself to start a number

of those courses, I just cannot spend hours going through that kind of

basics anymore.

Most courses will stop at some point stop, inviting you to do your

own coding to learn further. And that is mostly the point that it gets interesting.

So, none of the tutorials work and all stop where it gets interesting.

Furthermore, Python has a number of inconsistencies and bizarre concepts that

make the language harder to learn. Did I just say language? I meant languages,

because the changes between version 2 and 3 make it often impossible to

exchange programs between them.

As a tutorial exercise, I'll be rewriting my TCL/Tk application for

image administration in Python.

1.2. Quick language overview

1.2.1. Basic concepts

Python is an Object language. So most of the code will be in

classes or will be calling classes.

Python uses an indent to create blocks, in stead of { }, like in C/C++, Perl,

go, java, PHP, Scala etcetera or do/done or the likes. Python is very sensitive

to spacing. A block is ended with an empty line.

Comments are marked with #, which is normal for a scripting language.

Python has all the normal flow controls, while, for if-then-else. The syntax

is, that an indented block is started with a colon, for example:

for item in iterable_collection: # do something

Associative arrays (hashes in Perl) are called dictionaries

and behave more or less that same as Perl's hashes:

plaatjes = {

'molen' = 'mooi',

'straat' = 'lelijk',

'cavia' = 'lief',

}

for key, value in plaatjes.iteritems():

print key, value

molen mooi

straat lelijk

cavia lief

1.2.2. Let's have an argument

Python allows two types of arguments:

-

positional parameters

-

named parameters (called keyword parameters in Python)

Positional parameters are what every language uses. Keyword parameters in general get

an initial value and they are optional. As an example:

def hello (greet='hi',dest='all the people'): print greet, " to ", dest hello() hello(dest='you')

If you do not know (or care) how many positional parameters and/or keyword

parameters you get, you can use the c-style pointers:

def print_args(*args, **kwargs): print 'Positional:', args print 'Keyword: ', kwargs for key in kwargs.keys(): print "Key=",key," Value=",kwargs[key] if key == 'foo' : print "JA HOOR" print_args(1, 2, foo='bar', stuff='meep')

Obviously, it's nothing like c's pointers, but it's easier to remember like that.

1.2.3. Lists and references

A special place in hell should be reserved for the one who invented references in Python.

Consider the following:

a = [1, 2, 3] b = a a = [] print(a) print(b) a = [1, 2, 3] b = a del a[:] print(a) print(b) a = [1, 2, 3] b = a[:] del a[:] print(a) print(b)

Which gives as output:

[] [1, 2, 3] [] [] [] [1, 2, 3]

Obviously.

This can only be explained by the fact that

a = [1, 2, 3]

assigns a reference to the list

[1, 2, 3]

to the variable

a

and the line

b = a

assigns the value of a to b. That means that now,

a

and

b

both have a reference to the same

[1, 2, 3]

So when we do

a = []

a will be a reference to an empty list and b will still have a reference to the original list.

However, if I start doing operations on a list with

del a[:]

it affects the

list

and not the reference

to

the list. So that means that

b

(which is a reference to the same list) will now also point to the empty list.

Finally,

b = a[:]

forces a copy of a. So, because it is a copy, emptying a

will not empty b.

Pythons garbage collector for orphans seems effective enough, so you don't have to worry

about lists that are unrefferencable.

1.2.4. Tuples

Tuples are lists that you cannot change. Because they are static, they are faster.

And they use different parentheses.

That is all there is to know about them.

Many Python zealots will start talking about mutable and immutable objects. They will

also point to semantics, for example:

import time time.localtime() (2008, 2, 5, 11, 55, 34, 1, 36, 0)

where, if you delete the days, the minutes become hours. So this is why you

have time in tuples instead of lists.

1.2.5. Variable scoping

Because Python does not allow you to scope variables explicitly (PEP 20:

Explicit is better than implicit), Python uses the following rules:

-

If a variable is declared global it is assumed to be part of the global namespace.

-

If a variable is declared nonlocal it is part of the parent namespace.

-

If you assign a value to a variable, it is assumed to be part of the local namespace, from the beginning of that context.

-

If you do not assign anything to a variable, it assumed implicitly to be part of the parent namespace

-

Mutating an object (for example deleting parts of a list) is not considered as an assignment

The real fun starts when there are multiple nested namespaces...

1.3. Input Output

In the previous sections, al number of

print

statements have been used.

Reading stdin is a bit more difficult. If you want to read a number,

you can use:

value=input('prompt')

However, if you need a string as input, you must use:

value=raw_input('prompt')

2. Tkinter

Tkinter is a Python module for the TK-toolkit.

2.1. Hello, world

A first "Hello world" looks like

this:

#!/usr/bin/python import Tkinter as tk root = tk.Tk() w = tk.Label(root, text="Hello world!") w.pack() root.mainloop()

which gives the following window:

Which is nice. But what did we do?

import Tkinter as tk

So we imported a module Tkinter and we say we'd like to call it

tk

from now on. It is possible to just

import Tkinter

but then, instead of using

root = tk.Tk()

you would use

root = Tkinter.Tk()

and so on.

A lot of the rest is fairly standard Tk. So

compare

Python

|

TCL/Tk

|

root = tk.Tk()

|

|

w = tk.Label(root, text="Hello world!")

|

label .hello -text "Hello, World!"

|

w.pack()

|

pack .hello

|

and you'll see it is basically the same.

At the end, we do the

root.mainloop()

which starts the tk event loop. This is the moment that Python starts the

tk loop. In TCL, this is done automatically.

2.2. Hello again

Python uses classes. That means that you generally create classes to do

something for you.

#!/usr/bin/python from Tkinter import * class App: def __init__(self, master): self.frame = Frame(master) self.frame.pack() self.button = Button( self.frame, text="QUIT", fg="red", command=self.frame.quit ) self.button.pack(side=LEFT) self.hi_there = Button(self.frame, text="Hello", command=self.say_hi) self.hi_there.pack(side=LEFT) def say_hi(self): print "hi there, everyone!" root = Tk() app = App(root) root.mainloop() root.destroy()

Let's analyze what we did. First, we created a class

App

with two methods,

-

init

-

say_hi

The method

__init__

is a standard name. The method gets called

after

the object is created.

__init__

is not (as some less rigorous people seem to think) a constructor. The real constructor

is called

__new__(cls, *args, **kwargs)

In general, Python uses a lot of

__init__

and very seldom

__new__.

The first argument to all methods is

self.

The reason for this is that Python likes to state all sort of things explicitly.

The fact that there is an inconsistency between the calling of a method (where

self

is always missing) and the declaration does not seem to be a problem.

So we need to learn when explicit is required and when not.

The

App

object contains a number of Tk objects:

-

frame (which is a Frame)

-

button with quit

-

button with hello

All of these objects get a prefix of

self

because, in Python, there is no explicit variable declaration.

It is worth noting that the

self.frame.quit

quits the application (the main loop)

2.3. Tkinter widgets

Most of the widgets are the same as in Perl/Tk or TCL/Tk, and the syntax

example with the buttons above should make them usable.

Widget

|

Description

|

Button

|

A simple button

|

Canvas

|

Structured graphics.

|

Checkbutton

|

Represents a variable that can have two distinct values.

|

Entry

|

A text entry field.

|

Frame

|

A container widget.

|

Label

|

Displays a text or an image.

|

Listbox

|

Displays a list of alternatives.

|

Menu

|

A menu pane.

|

Menubutton

|

A menu button.

|

Message

|

Display a text.

|

Radiobutton

|

Represents one value of a variable that can have one of many values.

|

Scale

|

Allows you to set a numerical value by dragging a “slider”.

|

Scrollbar

|

Standard scrollbars for use with canvas, entry, listbox, and text widgets.

|

Text

|

Formatted text display.

|

Toplevel

|

A container widget displayed as a separate, top-level window.

|

LabelFrame

|

A variant of the Frame widget that can draw both a border and a title.

|

PanedWindow

|

A container widget that organizes child widgets in resizable panes.

|

Spinbox

|

A variant of the Entry widget for selecting values from a range or an ordered set.

|

As an example, a simle way to display an image is:

from Tkinter import * root = Tk() canvas = Canvas(root, width = 400, height = 400) canvas.pack() img = PhotoImage(file="/links/diaadm/images/fullsize/00125.gif") canvas.create_image(0,0, anchor=NW, image=img) mainloop()

3. Mariadb

3.1. Intro

All my data is currently stored in a Maria DB

and therefore it is necessary to use the Mariadb. The format

is simple: a single table holds all the data.

Name

|

Type

|

Description

|

number

|

INTEGER

|

Unique key for the image

|

type

|

VARCHAR(255)

|

The directory under /links/diaadm where the image is placed

|

file

|

VARCHAR(255)

|

The file name for the image

|

year

|

INTEGER

|

The year that the picture is made

|

month

|

INTEGER

|

The month that the picture is made

|

descr

|

VARCHAR(4096)

|

A short description, using many keywords

|

GPS_Latitude

|

VARCHAR(255)

|

Location where the picture is taken, if available

|

GPS_Longitude

|

VARCHAR(255)

|

Location where the picture is taken, if available

|

GPS_Altitude

|

VARCHAR(255)

|

Location where the picture is taken, if available

|

ISO_equiv

|

VARCHAR(255)

|

Copy of the JPEG header, if the data is available

|

Aperture

|

VARCHAR(255)

|

Copy of the JPEG header, if the data is available

|

Exposure_time

|

VARCHAR(255)

|

Copy of the JPEG header, if the data is available

|

Focal_length

|

VARCHAR(255)

|

Copy of the JPEG header, if the data is available

|

All sorts of improvements can be made (a perceptual hash can be created, keywords

in the description can get their own table), but that will be a later concern.

3.2. Sample program

From the Internet, I retrieved the following python script.

#!/usr/bin/python

import mysql.connector as Mariadb

mariadb_connection = mariadb.connect(user='diaadm', password='diaadm', database='diaadm', host='127.0.0.1')

cursor = mariadb_connection.cursor()

#retrieving information

some_name = 'l-j'

cursor.execute("SELECT type,file,descr FROM diaadm WHERE descr RLIKE %s", (some_name,))

for tpe, f, descr in cursor:

print("Type: {}, File: {}, Description: {}").format(tpe,f,descr)

Before I go into the details, I encountered a number of problems. First problem:

Traceback (most recent call last): File "maria.py", line 2, in <module> import mysql.connector as mariadb ImportError: No module named mysql.connector

This says that the module is not installed. So that means that you should install

the modules, using

gslapt

(or whatever your distributions flavor is)

or using

pip install.

Second problem:

Traceback (most recent call last): File "maria.py", line 4, in <module> mariadb_connection = mariadb.connect(user='diaadm', password='diaadm', database='diaadm', host='127.0.0.1') File "/usr/lib64/python2.7/site-packages/mysql/connector/__init__.py", line 179, in connect return MySQLConnection(*args, **kwargs) File "/usr/lib64/python2.7/site-packages/mysql/connector/connection.py", line 95, in __init__ self.connect(**kwargs) File "/usr/lib64/python2.7/site-packages/mysql/connector/abstracts.py", line 719, in connect self._open_connection() File "/usr/lib64/python2.7/site-packages/mysql/connector/connection.py", line 206, in _open_connection self._socket.open_connection() File "/usr/lib64/python2.7/site-packages/mysql/connector/network.py", line 475, in open_connection errno=2003, values=(self.get_address(), _strioerror(err))) mysql.connector.errors.InterfaceError: 2003: Can't connect to MySQL server on '127.0.0.1:3306' (111 Connection refused)

A MySQL client on Unix can connect to the mysqld server in two different ways:

-

By using a Unix socket file,

-

by using TCP/IP, which connects through a port number.

My TCL/Tk script connected to a socket, which is more secure, because you do not have to expose

the TCP-port. Apparently, as a default, Python's module uses a network connection.

Searching through the Internet did not turn up a quick solution to make Python behave

more securely, therefore, I restarted mariadb with

# SKIP="--skip-networking"

commented out in

/etc/rc.d/rc.mysqld.

3.3. Commitment

Contrary to the other languages I use (Perl, TCL) I use frequently, Python

turns autocommit off by default. Also, the mysql CLI starts with autocommit

on. But Python's PEP0249 states:

Note that if the database supports an auto-commit feature, this must be initially off. An interface method may be provided to turn it back on.

The problem is that if a session that has autocommit disabled ends without explicitly committing the final transaction, MySQL rolls back that transaction.

So, you have three choices:

-

Turn on autocommit

-

Explicitly commit your changes

-

Loose your data

Turning on autocommit can be done directly when you connect to a database:

import mysql.connector as mariadb connection = mariadb.connect(user='testdb', password='testdb', database='testdb', host='127.0.0.1',autocommit=True)

or separately:

connection.autocommit=True

Explicitly committing the changes is done with

connection.commit()

Note that the commit is done via the connection to the database, not via the

cursor.

4. Design issues

Upto here, everything was just more or less copying the orignal

TCL/Tk functionality in Python. However, where TCL/Tk code stays relatively compact,

with Pithon I now have a

script that is about the same number of lines

but implements only a very small part of the functionality. This is a strategy that is

not sustainable.

4.1. Splitting the GUI

In the TCL/Tk version it was one simple GUi; the tree-structure that the GUI has

is natural to that language.

In Python, it is not. So, in order to get a better and more readable code, we

have to create objects that provide a more high-level view of the GUI, instead

of the low-level Tk components.

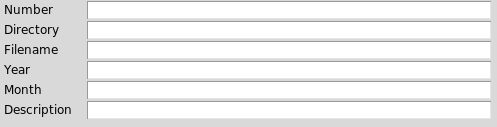

4.1.1. Entryfields

As a first, I have a number of entry fields that are preceeded by a label that

tells what information should be in the entry field.

So, the combination of a label with an entry field is a good candidate for

an object.

class entryfield(object): def __init__(self,parent,label='text'): self.fieldframe=tk.Frame (parent) self.fieldframe.pack(side=tk.TOP) self.fieldname=tk.Label(self.fieldframe, text=label ,width=10,anchor='w') self.fieldname.pack(side=tk.LEFT) self.fieldvalue=tk.Entry(self.fieldframe, width=50) self.fieldvalue.pack(side=tk.RIGHT) def set(self,value='text'): self.fieldvalue.delete(0,tk.END) self.fieldvalue.insert(0,value) def get(self): return(self.fieldvalue.get())

And with that object, creating the part of the GUI in the picture above becomes:

self.fieldnumber=entryfield(self.fieldframe,'Number') self.fielddir=entryfield(self.fieldframe,'Directory') self.fieldfilename=entryfield(self.fieldframe,'Filename') self.fieldyear=entryfield(self.fieldframe,'Year') self.fieldmonth=entryfield(self.fieldframe,'Month') self.fielddescr=entryfield(self.fieldframe,'Description')

That is clearly more readable than the endless repeats of the tk.Frame, tk.Label, tk.Entry

and their packs.

You will notice, that their are a number of assumptions that make this object rather specific

for my GUI. The size of the entry fields and labels are fixed, packing is always TOP etcetera.

This makes the entryfield object good for this GUI, but perhaps a bit less re-usable.

4.1.2. Multilist

The object of the next object is to create a more reusable object.

The problem is that we have multiple list boxes that must scroll synchronously

and with a scrollbar. This functionality existed in the TCL version and in the

one-big-gui version, so the main problem is to create a more generally usable

object.

class multilist (object) :

def __init__ (self,parent,columns=1,height=50,width=10) :

self.listframe=tk.Frame (parent)

self.listframe.pack()

# The listframe contains 4 lists and a scrollbar which are synchronized

self.sb = tk.Scrollbar(self.listframe, orient='vertical')

self.cols=[]

self.select=[]

for i in xrange(columns):

self.listnr=tk.Listbox (self.listframe, yscrollcommand=self.yscrollnr)

self.listnr.config(height=height,width=width)

self.listnr.bind('<<ListboxSelect>>',self.selectlist)

self.listnr.pack(side=tk.LEFT, expand=True )

self.cols.append(self.listnr)

self.sb.config(command=self.yview)

self.sb.pack(side=tk.RIGHT, fill='y')

def width(self,column=1,width=10):

print "set column ",column-1,' to ',width

self.cols[column-1].config(width=width)

def yscrollnr(self, *args):

for i in xrange(len(self.cols)):

self.cols[i].yview_moveto(args[0])

self.sb.set(*args)

def yview(self, *args):

for i in xrange(len(self.cols)):

self.cols[i].yview(*args)

def subscribe (self,function):

self.select.append(function)

def selectlist(self,event):

widget = event.widget

sel=widget.curselection()

if sel != ():

for f in self.select:

f(sel)

def clear(self):

for i in xrange(len(self.cols)):

self.cols[i].delete(0,tk.END)

def add(self, *args):

i=0

for val in args:

if i < len(self.cols):

self.cols[i].insert(tk.END,val)

i=i+1

else:

print "No column for $val"

Their are still a number of things that make this object

a bit specific, but it should be clear that there are a number of choices to

generalize its use.

First of all, the size (width and height) and the number of columns are

part of the call to

__init__.

It is also possible to adjust the column width on a per-column basis. Second,

the clear and add methods are used to manipulate the listbox contents.

Perhaps more interesting is the callback for a selection in the list. Instead

of calling a specific function,

external functions/objects/programs can subscribe to the select in the

listbox. So multiple functions can be called, just by subscribing to this event.

5. Style

The observation of Python's authors is that programs are more often read

than written. Therefore, they have adopted a specific style guide.

If you're writing Pythhon code, you should adher to it, because

-

others that see your programs will nag about it

-

if you're used to the style, it will be easier to read programs by others

There are some strange choices in the PEP8 standard. They make programs

needlessly long and, for a beginning Python programmer, harder to read.

They are also inconsistent in a number of ways.

This chapter does not explain the complete PEP8. I threw my code

through an on-line PEP8 checker and these are the errors that I found

in my code and my observation of them.

5.1. Spaces

Equal signs must have spaces around them, for example:

a = 1+1

Unless, the equal sign is used for an assignment of named arguments.

Other operators should not have spaces around them.

A comma should have a space after it.

a=function(arg1, arg2)

And parentheses do not get spaces.

The colon that is used for block starts should also not get a space:

def function(arg):

And comments start with

'# '

(hash-space).

5.2. Line length

Maximum line length is 80. Why? Because the IBM punch-card format, introduced

in 1928 had 80 columns.

5.3. Indent

One of the horrors of Python is it's attitude towards indents. Indents

are used to mark blocks. Indents are 4 spaces. Not a tab, four spaces.

Together with the 80-column limit, this also means a maximum

for nesting blocks (19), but if you hit that limit, you should

restructure your code anyway.

6. Common tasks

6.1. Configuration files

6.1.1. In Perl

What we're trying to accomplish ist the Python equivalent of

%config={};

open(CFG,"testfile.txt");

while (<CFG>){

s/#.*//;

if (/(\w+)=(.*)/){

$config{$1}=$2;

print "config{$1}=$2; $config{$1}\n";

}

}

So, a simple configuration file, with comments and simple a=b assignments.

While reding, we also want some sanity-checks, whitch is done by the matching

of the regular expressions. The result should be some form of hash/dictionary

in which we can lookup the values by text.

6.1.2. configobj

The Python-way seems to be to google if there is a module that does it

for you and then use that module. There are a number of modules that read

config files, and configobj seems the most simple one.

If it would work.

Try 1:

import configobj

config=configobj.configobj("testfile.txt")

Result:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "configobj.py", line 2, in <module>

import configobj

File "/home/ljm/src/learning_python/configobj.py", line 3, in <module>

config=configobj.configobj("testfile.txt")

TypeError: 'module' object is not callable

The type of

configobj.configobj

is a module. That is a bit unexpected. Especially since many answers on the Internet

suggest that

configobj

is the module and

configobj.configobj

should be the way to use it. But apparently, it is not.

import configobj print type(configobj) print type(configobj.configobj) print type(configobj.configobj.configobj)

gives:

<type 'module'> <type 'module'> <type 'module'> <type 'module'> <type 'module'> <type 'module'>

Try 2:

from configobj import configobj

which gives:

Traceback (most recent call last): File "configobj.py", line 2, in <module> from configobj import configobj File "/home/ljm/src/learning_python/configobj.py", line 2, in <module> from configobj import configobj ImportError: cannot import name configobj

Camel-humping the config obj results in yet another import error:

Traceback (most recent call last): File "configobj.py", line 2, in <module> from configobj import ConfiGobj File "/home/ljm/src/learning_python/configobj.py", line 2, in <module> from configobj import ConfiGobj ImportError: cannot import name ConfiGobj

This also means that none of the

configobj examples work. And because I don't understand what is happening

(behavior does not comply with any of the solutions that I got), I will abandon

this module.

6.1.3. ConfigParser

Another module that does the configuration is ConfigParser. It requires a

more complicates configuration file.

import ConfigParser

config = ConfigParser.RawConfigParser()

config.read('testfile.txt')

a=config.get('notes',"do")

print a

You must have a

[section header]

in the file, otherwise the module will fail.

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "configparser.py", line 4, in <module>

config.read('testfile.txt')

File "/usr/lib64/python2.7/ConfigParser.py", line 305, in read

self._read(fp, filename)

File "/usr/lib64/python2.7/ConfigParser.py", line 512, in _read

raise MissingSectionHeaderError(fpname, lineno, line)

ConfigParser.MissingSectionHeaderError: File contains no section headers.

file: testfile.txt, line: 1

eventhough the module is documented (

https://docs.python.org/2/library/configparser.html

), there is still a lot unclear about its

workings. Ah well, that also seems to be the Python way.

6.1.4. Import

There are some that suggest that using

import

and creating valid python code as config file is a good idea.

It is not.

Ofcourse, if everything is completely under control, and your users

won't put code in the config file, then it may not be so bad. But if

your user is anyone else but yourself, don't do this.

6.2. Command line arguments

6.2.1. Sys.argv

If you want to interact with anything beyond the most simplset, you need to import

sys.

In

sys

there is an array

sys.argv

that contains the arguments. Like everywhere else,

sys.argv[0]

contains the name of the script or program.

6.2.2. Getopt

A more or less standard way of parsing arguments is getopt. This

is available in C, Perl, Bashe and many others, and also in

Python. However, because it is standard, Python doesn't like it. The

official stance is that getopt is not deprecated, but argparse is more

actively maintained and should be used for new development.

The following sniplet shows the use of getopt:

#!/usr/bin/python

import sys, getopt

try:

opts, args = getopt.gnu_getopt(sys.argv[1:],"he:q:",["question=","exclamation="])

except getopt.GetoptError:

print sys.argv[0], '[-e excalamation ] [ -q question ]'

sys.exit(2)

for opt, arg in opts:

if opt == '-h':

print sys.argv[0], '[-e excalamation ] [ -q question ]'

sys.exit()

elif opt in ("-q", "--question"):

print arg,'?'

elif opt in ("-e", "--exclamation"):

print arg,'!'

print 'arg=',args

Note that

getopt.gnu_getopt

gets

sys.argv[1:]

as list of options.

sys.argv[0]

contains the name of the script and would therefore mess-up the

argument parsing.

We used

gnu_getopt

because otherwise, parsing of the flags stops when the first non-flag

argument is encoutered.

The result is shown below.

$ python getops.py -q question answer --exclamation yes oh question ? yes ! arg= ['answer', 'oh']

6.2.3. agparse

Agparse is at the moment the prefered option to parse command line arguments.

It is more advanced than getops, and it has a nice self-documenting feature.

6.3. Regular expression matching

If there's anything Perl is good in, it is handling regular expressions.

In Python, this is made complicated. As if the goal is to discourage the use.

First: it is not standard in Python.

It is an add-on that needs to be imported.

import re

7. Evaluation so far

I now have implemented exactly the same functionality in Python as

I had available in the TCL/Tk script. It is now time for a short

evaluation.

7.1. Speed

The Python script is noticably slower than the TCL/Tk

equivalent, epecially at start-up.

Something needs to be done about that otherwise Python scripts

become unusable.

The speed differnce is mostly in three places:

-

start-up

-

looping over the mysql-cursor

-

adding items to listboxes

The way I found this is by putting time print out

in specific functions:

from datetime import datetime def printnow(string): dt = datetime.now() print string, dt.second, dt.microseconds

and calling this

printnow

at specific places in the code.

You can ofcourse add

dt.minutes

but if the execution would require me to add the minutes,

I would abandon any further exploration of Python.

The result for the looping over the cursor ('cursor.executed' to

'copied to the list') are 1.3 seconds, as can be seen below:

get_selection 45 470185 cursor.executed 46 249354 copied to the list 47 554510 showlist start 47 554571 list cleared 47 633019 list filled 48 351590

The complete update of the listbox from the database is 2.8 seconds, which is

clearly much more than the almost instantanous response from TCL/Tk.

7.2. Code size

Python's code size in lines is significantly larger than TCL/Tk.

Python is a language that likes to do everything vertically. With

a maximum linesize of 80 characters, the codesize in lines quickly

becomes very large. The python version is 549 lines, and the TCL/Tk

is 337. In characters, Python is more than 75% larger.

7.3. Readability

Code from Python is marginally better readable. My screen is (vertically)

around 80 lines, which makes it impossible to get a good overview of sections

in the Python code in one screen. The punch-card restriction of 80 columns,

compared with the 180 columns of the terminal screen, makes it feel like

Python has made some odd choices.

7.4. Variable typing

One thing that is bewildering is the strong typing of Python

in combination with its dynamic typing.

In Perl, you can:

$a=2; $b="1+1=".$a; print $b;

to get "1+1=2".

In Python, this results in:

>>> a=2 >>> b='1+1=' + a Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> TypeError: cannot concatenate 'str' and 'int' objects

Note that you can assign

a='2'

even after it once was an integer.

That is called dynamic typing.

The combination of dynamic typing and strong typing gives

additional constructions like:

b='1+1={0}'.format((a))

which require quite a bit of Python specific reasoning to justify.

7.5. Libraries

Python has a lot of libraries that do different things, and many that do

the same thing. There is no way to tell if these libraries will be continued,

if they are part of standards or anything like that.

Further more, all sorts of installation methods are used, from

slapt-get

to

easyinstall

and

pip install

and let's not forget compiling from source.

The libraries are also all over the place; a standardization

in location seems difficult. Add to this the version 2 and version 3

problems and the frameworks, and you'll get

XKCD's installation

of Python.

8. References

I used a number of resources to learn Python. Some have

far more elaborate texts on the subject.

there are ofcourse other sources of information, but this

is what I used.

I have not listsed all the google searches that helped

me with specific questions.

http://effbot.org/tkinterbook/

An introducyion to Tkinter

https://www.programiz.com/article/python-self-why

the explanation of

self

in python classes

http://spyhce.com/blog/understanding-new-and-init

for the difference between

__new__

and

__init__.

http://www.mysqltutorial.org/python-mysql/

for the mysql interface.

http://pep8online.com/

for checking PEP8 compliancy.